Ratcliffe-on-Soar Power Station

| Ratcliffe-on-Soar Power Station | |

|---|---|

Ratcliffe-on-Soar Power Station Viewed from the east in September 2002 | |

| |

| Country | England |

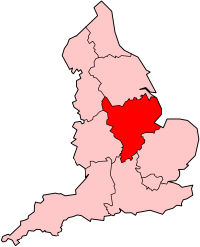

| Location | Nottinghamshire, East Midlands |

| Coordinates | 52°51′55″N 1°15′18″W / 52.865268°N 1.255°W |

| Status | Decommissioned |

| Construction began | 1963[1] |

| Commission date | 31 January 1968 |

| Decommission date | 30 September 2024 |

| Owner | Uniper |

| Operators | Central Electricity Generating Board (1968–1990) Powergen (1990–2002) E.ON UK (2002–2015) Uniper (2015–present) |

| Thermal power station | |

| Primary fuel | Coal |

| Cooling towers | 8 |

| Power generation | |

| Units decommissioned | 4 × 500 MW |

| Nameplate capacity | 2,116 MW |

| External links | |

| Website | Uniper/Ratcliffe-on-Soar |

| Commons | Related media on Commons |

Ratcliffe-on-Soar Power Station is a decommissioned coal-fired power station owned and operated by Uniper at Ratcliffe-on-Soar in Nottinghamshire, England. Commissioned in 1968 by the Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB), the station had a capacity of 2,000 MW. It was the last remaining operational coal-fired power station in the UK, and closed on 30 September 2024, marking the end of coal-powered electricity generation in the United Kingdom.

The power station occupies a prominent position next to the A453 road, close to junction 24 of the M1 motorway, the River Trent and the Midland Main Line (adjacent to East Midlands Parkway railway station) and dominates the skyline for many miles around with its eight cooling towers and 199 m (653 ft) tall chimney.

History

[edit]

The public enquiry for the station took place at County Hall, Nottinghamshire from 8 January 1963.[2] It was approved by the government on 29 August 1963.[3]

Construction

[edit]The construction of the power station began in 1963[1] and it was completed in 1967.[1][4] The station began generating power on 31 January 1968.[5]

The architects were Godfrey Rossant and J. W. Gebarowicz of Building Design Partnership. White cladding was used on the boiler and turbine houses and the end elevations had vertical bands of glazing to emphasise their verticality, the four concrete coal bunkers projected above the roof-line.[6] The structural engineer was C.S. Allott.[7]

Design and specification

[edit]The station has four units, each consisting of a coal-fired boiler made by Babcock & Wilcox driving a 500 megawatt (MW) Parsons generator set. The four boilers are rated at 435 kg/s, steam conditions were 158.58 bar at 566 °C, with reheat to 566 °C.[8] This gave the station a total generating capacity of 2.116 GW, equivalent to the electricity demand of approximately 2 million people.[9] There are 4 × 17.5 MW auxiliary gas turbines on the site; these were commissioned in December 1966.[8]

Ratcliffe power station is supplied with coal and other bulk commodities by rail via a branch off the adjacent Midland Main Line (MML). Rail facilities include a north facing junction off the MML slow lines, two tracks of weighbridges, coal discharge hoppers, and a flue gas desulfurisation discharge and loading hopper. There was formerly a fly ash bunker and loading point with a south-facing connection to the MML; this was extant in 1990 but had been demolished and disconnected by 2005.[10][11][12]

Electricity production

[edit]In 1981, the station was burning 5.5 million tonnes of coal a year, consuming 65% of the output of south Nottinghamshire's coal-mines.[13] The last of Nottinghamshire's collieries, Thoresby Colliery, has since closed in 2015. Emissions of sulphur dioxide, which cause acid rain, were greatly reduced in 1993 when a flue gas desulphurisation system using a wet limestone-gypsum process became operational on all of the station's boilers. Emissions of oxides of nitrogen, greenhouse gases which also cause damage to the ozone layer, were reduced in 2004 when new equipment was fitted to Unit 1 by Alstom.[14]

In 1975/76 and again in 1986/87 Ratcliffe was presented with the Hinton Cup, the CEGB's "good house keeping trophy". The award was commissioned by Sir Christopher Hinton, the first chairman of the CEGB. On 11 February 2009, Unit 1 became the first UK 500 MW coal-fired unit to run for 250,000 hours.[15]

On 2 April 2009, E.ON UK announced it had installed a 68-panel solar photovoltaic array at the power station "to help heat and light the admin block, saving an estimated 6.3 tonnes of carbon dioxide per year".[16]

Uniper has its Technology Centre at the site, where it carries out research and development on power generation.

Environmental performance

[edit]In 2009, the plant emitted 8–10 million tonnes of CO2 annually,[17] making it the 18th-highest CO2-emitting power station in Europe.[18]

Ratcliffe power station is compliant with the Large Combustion Plant Directive (LCPD),[19] an EU directive that aims to reduce acidification, ground level ozone and particulate matter by controlling the emissions of sulphur dioxide, oxides of nitrogen and particles from large combustion plants. To reduce emissions of sulphur the plant is fitted with flue gas desulphurisation, and also with a Boosted Over Fire Air system to reduce the concentration of oxides of nitrogen in the flue gas.[15]

Ratcliffe power station was the first in the United Kingdom to be fitted with selective catalytic reduction (SCR) technology, which reduces the emissions of nitrogen oxides through the injection of ammonia directly into the flue gas and passing it over a catalyst.[20]

Environmental protests

[edit]

On 10 April 2007, eleven environmental activists from a group called Eastside Climate Action were arrested after they entered the power station and climbed onto equipment in order to draw attention to greenhouse gas emissions from coal-fired power stations, when E.ON UK was proposing to build more.[21]

In 2009, the station was the intended target of protesters when, in the early hours of 14 April, police arrested 114 people at Iona School who were planning to disrupt[22] the running of the power plant. Those arrested were not charged and soon released on bail. Later, 26 of those arrested were charged with conspiracy to commit aggravated trespass, a charge that carries a maximum six months sentence.[23] Twenty of these activists, having admitted that they planned to break into the power station, were found guilty of conspiracy to commit aggravated trespass. When sentencing 18 of these protesters, in December 2010, the judge called them "...decent men and women..." and handed out community orders with only two having to pay reduced expenses.[24] The charge against the six pleading not guilty was dropped when it was revealed that Mark Kennedy of the Metropolitan Police had been working as an undercover infiltrator for the National Public Order Intelligence Unit and had played a significant role in organising the action.[25] Additionally, recordings made by Kennedy should have been made available to the Crown Prosecution Service and the defence team. Following these revelations the 20 convicted activists appealed, and their convictions have since been quashed.[26]

Between 17 and 18 October 2009, protesters from Climate Camp, Climate Rush and Plane Stupid,[27] took part in The Great Climate Swoop at the site. The police arrested 10 people before the protest began on suspicion of conspiracy to cause criminal damage.[28] Some 1,000 people took part, and during the first day groups of up to several hundred people pulled down security fencing at a number of points around the plant.[29] Fifty-six arrests were made during the protest and a number of people were injured, including a policeman, who was airlifted to hospital but later discharged.[30]

Closure and future

[edit]In June 2021, the site was listed as a possible location for the world's first nuclear fusion power plant.[31][32] However, it was withdrawn from the shortlist in January 2022.[33]

In response to the 2021 United Kingdom natural gas supplier crisis, the decommissioning of one of the station's 500-megawatt units, originally planned for September 2022, was delayed.[34][35] Upon the closure of Kilroot Power Station in Northern Ireland in September 2023, it became the last coal-fired power station in the UK.[36][37] In January 2024, all four of its generating units had to be run together for the final time in response to high demand from cold weather. In April 2024, one unit was placed into "preservation" mode, in advance of plant shutdown,[38] and in June 2024, the last train of coal was delivered for burning at the power station.[39] The station closed for power generation on 30 September 2024 at midnight,[40][41][42][43][failed verification] with the turbo generator de-syncing from the National Grid just after 15:00 on 30 September,[44] ending 142 years of British coal power[45][46][47][48] and precipitating a two-year decommissioning process.[49][50]

The site is planned to be redeveloped, and a Local Development Order (LDO) has been established to achieve this.[51]

See Also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Appendix 1". High merit post war coal & oil fired power stations (PDF). Historic England. p. 3. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Nottingham Evening News. January 1963. p. 1.

- ^ Nottingham Evening Post. 29 August 1963. p. 1.

- ^ Locker, Joseph (22 April 2022). "Plan to detonate huge cooling towers at Ratcliffe-on-Soar power station in 'blow-down' event". Nottingham Post. Retrieved 18 September 2024.

- ^ Nottingham Guardian. 1 February 1968. p. 3.

- ^ Clarke, Jonathan (2013). High merit: existing English post-war coal and oil-fired power stations in context. London: Historic England. pp. 17–18.

- ^ Nottingham Evening Post. 12 October 1963. p. 9.

- ^ a b Handbook of Electricity Supply Statistics 1989. London: The Electricity Council. 1990. pp. 4 & 8. ISBN 085188122X.

- ^ "Ratcliffe-on-Soar". E.ON UK. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007.

- ^ Jacobs, Gerald (1990). London Midland Region Track Diagrams. Exeter: Quail. pp. 4A. ISBN 0900609745.

- ^ Jacobs, Gerald (2005). Railway Track Diagrams Book 4: Midlands & North West. Bradford on Avon: Trackmaps. pp. 4A. ISBN 0954986601.

- ^ Bridge, Mike (2013). Railway Track Diagrams Book 4: Midlands & North West. Bradford on Avon: Trackmaps. pp. 4A. ISBN 978-0-9549866-7-4.

- ^ "The Nottinghamshire Heritage Gateway > Themes > The coal industry in Nottinghamshire > Overview". www.nottsheritagegateway.org.uk. Archived from the original on 20 May 2009.

- ^ "ALSTOM wins major NOx reduction order in UK". 9 January 2004. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012.

- ^ a b "E.ON UK - Ratcliffe-on-Soar". E.ON UK. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007.

- ^ "The future's bright at E.ON's Ratcliffe-on-Soar Power Station". E.ON UK. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011.

- ^ See table provided by E.ON UK on

- ^ "Protesters target E.ON's Ratcliffe plant". Reuters. 31 August 2009.

- ^ "Large combustion plant directive". E.ON UK. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007.

- ^ "Emission control ensures power station's survival". World Pumps. 2015 (10): 28–29. 1 October 2015. doi:10.1016/S0262-1762(15)30340-0.

- ^ "Protest is held at power station". BBC News. 10 April 2007. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ "Ratcliffe activists found guilty of coal station plot". The Guardian. 14 December 2010. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "Police hold 114 in power protest". BBC News. 13 April 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ "Ratcliffe-on-Soar power station protesters sentenced". BBC News. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ Evans, Rob; Lewis, Paul (9 January 2011). "Undercover officer who spied on green activists". The Guardian.

- ^ "Power station activists win appeal over missing police spy's tapes". The Guardian. 19 July 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ^ "Hundreds of protesters expected to 'take over' Ratcliffe-on-Soar power station". This is Nottingham. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ Dwyer, Danielle (17 October 2009). "Ten held ahead of power station protest". The Independent. London. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ "Climate protest enters second day". BBC News. 18 October 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ "Power station demonstration ends". BBC News. 18 October 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ "Coal-fired power stations listed in 'UK's first' fusion plan". BBC News. 11 June 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ "Potential sites for fusion power plant identified". BBC News. 11 June 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ "Ratcliffe-on-Soar power site withdrawn from world-first power station race". The Business Desk. 21 January 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Lawson, Alex (28 August 2022). "Closure of coal power station set to be delayed to prevent UK blackouts". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Pridmore, Oliver (31 August 2022). "Ratcliffe-on-Soar power station unit may stay open for 'back-up electricity' this winter". NottinghamshireLive. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ Barlow, Jamie (5 August 2021). "Uniper confirms when coal-fired power station at Ratcliffe-on-Soar will close". Nottingham Post. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ "West Burton A - the past and the future of power?". BBC News. 1 April 2023. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ Ambrose, Jillian (21 April 2024). "Powering down: end times for the UK's final coal-fired station". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ Hare, Simon (30 June 2024). "Power station's last coal delivery arrives by rail". Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ Vaughan, Adam; Davies, Matilda (27 September 2024). "The day coal dies". www.thetimes.com. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ Brinded, Alex. "Last UK coal power-station closes". www.iom3.org. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ Largue, Pamela (30 September 2024). "UK's last coal-fired power plant closes its doors for the final time". Power Engineering International. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ "Britain's last coal-fired electricity plant is closing. It ends 142 years of coal power in the UK". AP News. 30 September 2024. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ "UK becomes first G7 nation to exit coal-fired power". Sky News. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ Armstrong, Jeremy (29 September 2024). "Britain's last coal power station to close after 142 years marking end of an era". The Mirror. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ Mavrokefalidis, Dimitris (29 September 2024). "'King Coal is dead': UK bids farewell to coal as last power station closes today". Energy Live News. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ Twidale, Susanna (30 September 2024). "Britain to become first G7 country to end coal power as last plant closes". Reuters. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ Ambrose, Jillian (29 September 2024). "End of an era as Britain's last coal-fired power plant shuts down". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ "GB Railfreight completes historic final coal delivery and names a locomotive 'Ratcliffe Power Station'". Uniper Energy. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ "Ratcliffe-on-Soar: Neighbours prepare for end of power station". BBC News. 16 September 2024. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ "Ensuring a sustainable future for a coal-fired power station site approaching closure". ARUP. 21 May 2024. Archived from the original on 7 September 2024. Retrieved 24 September 2024.